| The Priestess and the Slave by Jenny Blackford Chapter One—Thrasulla, The Priestess |

Delphi, around 491BC THE SPARTAN KING, KLEOMENES, had the eyes of a rabid wolf. He was half- mad with cunning. Perialla could not see it, though it was clear to me as daylight. Even now, I cannot understand why Delphic Apollo so blinded his senior Pythia to the madness of the man who wished to use her. The meeting that day, in the best room of the house that we three priestesses of Apollo shared at Delphi, was Kobon’s idea—yet another of his endless self-serving machinations. His father, Aristophantos, was the richest man in Delphi; he swaggered the streets of the town as if the citizens of all Phokis had made him tyrant. At 60, Aristophantos had the look of a proud old bull, master of the herd, and showed no sign of approaching death. It would be decades before plump Kobon inherited his father’s wealth; while he waited, he indulged himself in power politics. He glowed with self-satisfaction on the day he brought Kleomenes, king of the Spartans, to meet us in our blue-painted andron—the formal dining room which would have held men’s drunken dinner-parties, if Perialla, Diodora and I had not been female, and celibate in Apollo’s service. Kleomenes pretended to pay attention as Kobon droned on about the eternal link of friendship between the peoples of Sparta and Delphi, but one sandaled royal foot was quietly tapping on the floor, betraying the king’s impatience. I could only bear to listen to one word in five of Kobon’s speech; even that much could have put Prometheus to sleep, despite the agony of the eagle tearing at his liver. The small fire in the hearth of the andron made it cozy, and the carved wooden chairs that the slaves had set in a rough circle were all too comfortable. It would have been far too easy for me to have closed my eyes and fallen into dreams. Instead, I gossiped. “If Kobon doesn’t stop fiddling with that new signet ring,” I whispered to Diodora behind my hand, “I’ll scream.” “There’s no way his wife would have let him buy that,” she whispered back. “She's pregnant again, and their eldest girl will need a dowry soon. The slaves tell me her periods started last year; her mother won’t want to wait too much longer before she gets the girl safely married. She’s no great beauty, either.” “Mmm,” I said. I’d heard the same things, and come to the same conclusion. “That ring looks expensive,” Diodora said. “The amethyst’s a good deep color, and the Gorgon on it was carved by a master.” Her fingers traced snake-symbols on her arm. “The workmanship is worth far more than the gold or the stone. I think Kleomenes has been generous to his friend Kobon.” If the prophecies Apollo gives through us are to be useful to those who seek them, we Pythiai need more than ordinary common sense. Good oracles are skilled judges of men and women, and of the little signs that give away their secret desires. When Apollo chooses us to serve him, we must be past the age of caring for men, or of men lusting for us. Fifty years in the world can teach an active mind more than it is comfortable to know of human nature. “Generous again,” I said. The gold chain that Kobon had mysteriously acquired last time Kleomenes visited Delphi still gleamed bright around his neck. As Kobon maundered on, he touched the new ring with a fleshy finger, and fingered the blue glass amulet that hung from the gold chain. He gazed at the Spartan king as a lapdog looks at its master. He did not see the madness in those flashing eyes. * * * My father killed a rabid wolf one winter, back when I was just an ordinary girl of twelve or so, gawky and thin—long years before I was taken by oracular Apollo to be a Pythia. Our dogs were barking as if the sky had fallen, and the sheep were baa-ing loud enough to make it fall. Father and I both went out to the snow- covered farmyard to see what was happening, leaving Mother with my siblings and the slaves indoors, crowded around the warmth of the hearth. The wolf was jumping up against the sheep-pen, snapping at the wood, taking no notice of the noisy dogs. Thick saliva dripped from its jaws. The winter sun was low over the gray-green waters of the Gulf of Corinth far below our stony farm, and the cliffs of Parnassos loomed above us; the wolf’s mad eyes seemed bright as torches in the weak late-afternoon light. Father called back our thin brown mongrel dogs. They slunk to him and cowered behind his legs. They knew the wolf was strangely dangerous; like me, they had a gift for reading the movements of the body. I stood beside my father, deliciously afraid, and glad to be away for once from the women and the endless weaving and spinning. A proper Hellene girl would have been terrified, I’m sure; my mother would have fainted with terror even to know a wolf was near. I, instead, was fascinated by the strangeness of the wolf, the panic of the sheep. “That wolf’s mad, Thrasulla,” Father said, holding out an arm to keep me safe behind him. “We mustn’t go too near. Fetch me the bow and a handful of arrows, will you? I’ll keep my eyes on the wolf. Go as fast as you can. Oh, and take the dogs with you, and lock them inside the house to keep them out of trouble.” I ran to the house with the dogs at my heels, found the bow that always hung near the front door, took arrows from the goatskin bag nearby. I closed the heavy door on the dogs behind me; Mother mightn’t like them being in the courtyard by day, but Father could explain later. Out at the sheep-pen, the wolf slavered and growled. Without a word, Father took the bow and one of the arrows from me and put an arrow neatly through the beast’ s hairy throat. It didn’t seem to notice; it kept jumping up the sides of the pen, frantic to reach the scared, silly sheep that milled pointlessly in circles. I handed Father another arrow, which he shot into its heart, then another. By the time my hands were empty, the wolf lay still on the snow, bleeding from wounds all over its throat and chest. I stood and looked, almost entranced. How strange to see the madness end in bloody death—far stranger than the neat, domestic deaths of ducks and geese destined for the cooking pot. “If he’d bitten the dogs, Thrasulla, they’d have been mad like him in a month or two,” Father said. He took the wolf’s corpse by its shaggy tail and started to drag it away from the sheep-pen. “Or like Glaukos, Nikes’ son?” I asked. I was fairly sure, but I wanted to check with the only person whose opinion I really trusted. Father turned, and looked hard at me. “Tell me about it, daughter,” he said. “It was while you were on campaign with the army last summer. Glaukos was bitten by a mad dog, and his father killed it, but too late. Mother went to try to help the family to heal him, but there was nothing she could do. Glaukos screamed nonsense day after day, and frothed at the mouth. They say he even hit out at his mother and the slaves, before he died. And he would drink nothing for days, though he must have been thirsty.” Father looked at me, his face serious. “You’re right. It is the same madness.” “I thought so.” Father’s frown deepened. “You see more than other children, Thrasulla. It’s not normal.” I shrugged. I’d never been normal. Mother had made that clear from the moment I first spoke—perhaps even before then, but I don’t remember that. All of the slaves were afraid of me. Ten or twenty times a day I caught them from the edges of my vision making the sign against the evil eye at me. I didn’t care. I asked, “So if that wolf had bitten me, I’d have been like Glaukos?” “Yes,” Father said, still dragging the wolf by the tail behind him. “Stay away from any sign of madness, daughter.” His tone of voice was odd. I could tell that he meant more than he said, but I was too young to untangle the strands of meaning—to understand what he was afraid to say to me. I just nodded. I would think about it at night, while the rest of the family snored. Sleep had never come easily to me, and tonight would be more difficult than usual, I knew, after the excitement. Father left the dead wolf on a bare patch of ground far from the sheep or the dogs. He said, “We must purify the carcass with fire.” We walked back towards the farmhouse, to the winter wood-pile. My father placed a load of kindling in my outstretched arms, and took an armful of heavier pieces of wood for himself. We stood together in silence, wrapped in our thick woolen cloaks—not elegantly, like Mother, but tightly against the snow-cold wind—and watched the fire burn until the wolf was nothing but ashes and gray lumps of bone. Father’s red-brown hair glowed in the fire’s light. Copyright (c) 2009 by Jenny Blackford |

| HADLEY RILLE BOOKS |

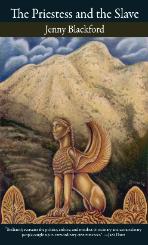

| Cover art (c) Rachael Mayo |

Book specifications:

Title: The Priestess and the Slave

Author: Jenny Blackford

Trade paperback: 112 pages

Release Date: April 15, 2009

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 inches

ISBN-13: 978-0-9819243-1-1

Price: $9.99 USD

Publisher: Hadley Rille Books

Title: The Priestess and the Slave

Author: Jenny Blackford

Trade paperback: 112 pages

Release Date: April 15, 2009

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 inches

ISBN-13: 978-0-9819243-1-1

Price: $9.99 USD

Publisher: Hadley Rille Books