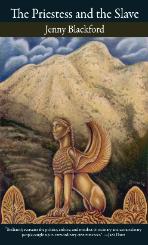

| The Priestess and the Slave by Jenny Blackford Chapter Two—Harmonia, The Slave |

Athens, Summer, 430BC THERE SHOULD HAVE BEEN nothing in Aristogeiton’s stomach except the water that I had trickled between the boy’s bleeding lips over the previous hour, but all the same he retched and groaned until the bowl I held was half-full of foul liquid. The smell in the boy’s bedroom was appalling, but a slave must cope each day with things that an Athenian citizen would never endure; I’d had twenty-two years of it, since I’d been born a slave. “I think that’s all for now, Harmonia,” the boy said, his voice wavering. “By all the gods, I hope so. That was horrible.” I wiped the boy’s raw, bloody mouth with a clean, damp cloth and settled him back onto his pillows. “Would you like more water?” I asked. For days, Aristogeiton had swallowed all the liquid anyone could dribble into his mouth, but he was still thirsty. “Soon,” he said, too quietly for my liking. “My mouth feels as if it’s on fire. But wait a little while, first, Harmonia. I’m so tired.” I carried the bowl to the door. Soon I would go and empty it into the cesspit in the courtyard—but not until he was asleep. Under the vomit in the bowl lurked Medusa’s face, painted in red, her tongue lolling from a too-wide mouth, snakes writhing in her hair. The painter had put the angry gorgon in the center of the bowl to avert evil, but the disease that had Aristogeiton in its foul jaws was not afraid of her—or of anything. The boy held up his right hand to me. “Am I dying, Harmonia?” he asked, his voice as brave as an eleven-year-old could make it. He was his father’s son and heir; he knew that he was expected to carry on the family name and bear a son to tend the family’s graves. “Of course you’re not dying, Aristogeiton,” I lied. “In a few years, you will be a strong hoplite soldier just like your father. You will fight the enemies of Athens and win great battles. And you will make wonderful sculptures, just like him.” “I will,” he said, half-smiling. “Yes, I will. I’ll make friezes for temples, and big, strong herms to stand guard at the front of people’s houses, and everything.” His swollen eyes closed. I closed my eyes, too, for a moment. I could not let the boy see me crying. Aristogeiton had always loved the herms in his father’s workshop, each with life- like cock and balls protruding from a smooth block of stone, and Hermes’ bearded head at the top. But it didn’t seem likely that the boy would ever grow up to carve one of them himself. Unless the gods intervened, he would die of this new disease that was sweeping Athens, this plague, and nothing I or anyone else could do would stop it. I was just one of the family’s female slaves, house-born in Athens. I did what I could to help the boy: bathing his head and his hot, reddened eyes; cleaning his ulcerated body; trickling water and thin barley porridge into his bleeding mouth; and stroking olive oil onto his congested, aching chest. It was not enough. Aristogeiton’s flesh was cool to the touch, but to him it felt like flames, and all the water in Athens could not cool the fire inside him. My master Pauson came to the sickroom door. He was not ill like his son, but the lines of his face were harsh in the midday light; they showed how little he had slept lately. He looked at the boy, then looked at me, questioning. “No change,” I mouthed. He pulled a light chair up to the other side of the bed. “You will get better now, Aristogeiton,” he said to his son. “I have given a sacrificial cake to Apollo Far- shooter on our courtyard altar. I promised him that, when you are well again, I will sacrifice a goat to him, and I will carve a statue for his temple from the finest Pentelic marble I can buy. Apollo will help us now. His arrows bring plagues and disease, but he is the Healer as well.” The boy grabbed at his father’s hand, and held it tight. Pauson kept talking, anxiously. Was he trying to convince the boy, or himself? “In a few days it will be the seventh of Hekatombaion, and Athens will celebrate Apollo’s yearly feast. The city will sacrifice countless fine cattle to the god, and he will be pleased with all of us. Apollo the Healer will cure you, I’m sure.” “Aristogeiton needs to sleep now, master,” I said. Really, it was the master who needed to sleep, and me. Soon enough, unless the healing god intervened, the boy would sleep quietly in his grave forever. The boy was worst at night, coughing and retching. The night before, he’d thrown up the contents of his stomach four, maybe five times. For the previous seven days and nights, my twin sister and I had nursed him together, dozing on a pallet in the corner when we could. The master had spent the nights in his own bedroom with his wife, as was fitting, but he looked as if he hadn’t slept any more than we had. At least Pauson wasn’t managing the sculpture workshop at the same time. With the Spartan army camped in the countryside less than a day’s march from Athens, just as in the previous summer, looting and burning, there was more demand for swords and shields than for the works of stone and marble that Pauson usually produced, and the war had put a stop to Perikles’ rebuilding of the temples up on the Akropolis. The master’s strong male slaves were earning good wages for him in an arms factory owned by his friend Drakes, making bronze weapons for Athenian citizens going off to war. “I will sit with my son for a while,” Pauson said, still holding Aristogeiton’s hand. “Go rest, Harmonia, and leave me alone with him.” Before I’d reached the door, Aristogeiton had a fit of coughing, and I ran back to his side. The boy’s breath was strangely fetid, like nothing I had smelled before. I took the cloth from his forehead, rinsed it in the jar of clean water at my feet, and wiped his face with it. I rinsed the cloth again, then lay it back on his flushed forehead to keep him cool. Pauson gave me an exhausted half-smile, and pointed at the door. “Go,” he said. “Rest.” * * * How could I rest? I was too worried—about my sister, even more than about Aristogeiton—and my mistress needed to know how her son was now. I nodded obediently to my master, but I carried the bowl of vomit to the cesspit in the corner of the courtyard and tipped it out, then drew fresh water up from the deep well, to rinse it thoroughly. My mistress Ismenia had most of the women of the house gathered around her in the courtyard, working, as if it was a normal day. The mid-summer sun was high in the sky, now, and the shady side of the courtyard, under the colonnade, was far cooler than the workroom upstairs where we spent most of our days. She’d set up the tall loom in the shade next to the kitchen wall, and was walking back and forth in front of it, pushing the shuttle with the thread through the vertical strands of fine-spun wool. Each pass my mistress made, tall, young Dosis beat the new thread upwards, compacting the weave into good, dense cloth. Ismenia was still elegant, despite everything. Her long, black hair was carefully piled up into a low bun, and one of the slaves had tied a ribbon around her head; her old-fashioned chiton draped gracefully from two brooches at her shoulders, and the overfold that hung down to her waist was patterned at the edge with fine blue and yellow lines. Unless you looked, you wouldn’t notice that her lovely eyes were red from crying, but I’d heard her in the night, when Aristogeiton was quiet. The mistress’ almost-nubile daughter, clever Philinna, sat on a stool nearby, spinning washed and carded wool into fine thread as if it might save her younger brother’s life, while a baby girl lay on the ground, trying to catch the spindle whorl in her tiny grasping hands. Expensive toys were scattered all around her: a rattle, a cart with wheels that really turned around, a man riding on a mule—but the spindle whorl moved in the sunlight, entrancing her. The baby belonged to Pauson’s moody sister Kalonike, who’d come to us after the Spartan army had marched over the Isthmus into Attika to ravage and burn the crops and houses of the countryside. Perikles, the strategos who’d led Athens to so many victories, had commanded all those who lived outside the city walls to retreat within their solid protection. Pauson had been happy to take in his difficult sister and her husband, Thaumas, when they’d arrived here, even though he’d said, apologetically, that this house in Athens was small by country standards. Soon, though, refugees from the countryside were camping out anywhere they could, in temples or on any empty land. Kalonike’s grown son wasn’t married, and lived with them on their farm, but he’d already been out on campaign when she and Thaumas had come here. Her husband was soon levied to serve as one of the four thousand hoplites whom Perikles took on his triremes to ravage the Spartans’ own coastline. It was only Kalonike and her baby here now, in Pauson’s house, and the foolish woman mourned her absent men as if they were dead. The two middle-aged female slaves whom Kalonike had brought to the house with her were busy carding wool, rubbing it on their thighs as they knelt on soft mats on the stones of the courtyard. They spoke to one another quietly in their barbarian tongue from far-off Syria, which I cannot understand. Their city had been captured in a small war, decades ago; the men were put to death, and the women and children enslaved. The two women seemed empty-headed when they spoke to us in the halting Greek that they’d picked up after they were enslaved. For all I knew, though, they could have been talking together about war and politics, or epic verse, or even the strange gods who live in the East, where they came from. Perhaps their lives were deeper and stranger than I ever understood. Copyright (c) 2009 by Jenny Blackford |

| HADLEY RILLE BOOKS |

| Cover art (c) Rachael Mayo |

Book specifications:

Title: The Priestess and the Slave

Author: Jenny Blackford

Trade paperback: 112 pages

Release Date: April 15, 2009

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 inches

ISBN-13: 978-0-9819243-1-1

Price: $9.99 USD

Publisher: Hadley Rille Books

Title: The Priestess and the Slave

Author: Jenny Blackford

Trade paperback: 112 pages

Release Date: April 15, 2009

Dimensions: 8.5 x 5.5 inches

ISBN-13: 978-0-9819243-1-1

Price: $9.99 USD

Publisher: Hadley Rille Books